Oct 6th, 2024 by rrchard

The Cradle

This painting was created in 1872 by Berthe Morisot. It depicts her sister, Edma Portillon, watching over her baby daughter Blanche. This work has become one of Morisot’s most famous paintings but was not very well received when it was created. Morisot was unable to sell it and it stayed in the family, later passing to Blanche Portillon, the baby pictured. This painting represents a theme of motherhood Morisot tries for the first time here and presents itself frequently in her other work. Many value the simplicity of this painting, highlighting the bond between mother and child without needing distraction. The composition of this painting is also something to note as there are lots of diagonals in it. Between the mother and baby, the fabric of the cradle, and the top of the cradle to the mother. I find it strange that The Cradle is revered as one of Marisot’s best works though it was not popular at the time of creation.

Eugène Manet on the Isle of Wight

Oct 6th, 2024 by rrchard

Eugène Manet on the Isle of Wight

This painting is of Eugène Manet looking out a hotel window at 2 passing women and a few boats at the shore. The work is by Berthe Morisot, who is the wife of the subject and the artist I am focusing on for my story. Morisot and Manet were married in December of 1874 and this work is from 1875. Morisot created this painting during their honeymoon, located on the Isle of Wight, Cowes specifically for this work. Some historians have analyzed Morisot’s choice to paint from inside with curtains shielding from outside. Scholars believe that this choice was made to represent the restrictions placed on women during the time.

During their honeymoon here Morisot painted many other works of their time on The Isle of Wight. These include Aboard a Yacht, Boats, Boats on the Quay, English Seascape, and of course, The Isle of Wight. She was clearly very inspired by this place. Her consistency of painting from small hidden points of view during this trip shows her reluctance to paint in public, based on the backlash and judgment she would have received.

One of Sally Mann’s Early works was At Twelve. A collection of photos about young gurls on the edge of adulthood. Young girls were often caught in the middle of wanting to be a child and wanting to grow up. Sally captures these photos of close family friends and relatives. These pictures are intended to show the problems young women faced and continue to face.

These young girls are just posing for a picture and it is up to the interpreter to take what they want from the photo. Most people took the innocence of these young girls out of the picture, and had there own interpretations. Girls are oftened sexualized and that is what Sally tried to portray in these images. It is also about how girls become women quickly. She really wanted to show that to be young in America is a time of excitement and possibilities.

There is no distinction between the time you are 12 to the time you become an adult. Are you an adult at 18 or 21? Legally you are at 18, but you cant purchase alcohol until you are 21. Not saying alcohol makes you an adult but, if you are an adult shouldn’t you be able to purchase it at the age of 18. From the time of your teenage years you are constantly learning more about your body and everything around you. Things you were to young to know or hear, are now things you often think about. A time where you once played with dolls and loved family time, now turned into hanging out with friends or boys and wanting to be away from your family.

This collection was mainly to show that no matter the innocence of a young girl, society is the issue. Society picks how they want to interpret the photos and society decided if something is frowned upon or not. However, I believe that is what Sally wanted. She wanted to show the world that it is them, and not the children or women in this world. The world sexualizes so many things and that is where problems began.

Proud Flesh

Sep 13th, 2024 by amsmith

Proud Flesh by Sally Mann is a collection of photos that show the decomposition of the body overtime. Sally Mann’s husband, Larry Mann, sufferers a disease called muscular dystrophy. Basically, that means your muscles weaken over time. He mostly has been losing muscle in hir right leg and left arm. The things he once was able to do easily, now causes him much pain.

When Sally began taking these photos for Proud Flesh, she used her husband as her art. Sally photographed Larry using a cumbersome process that goes back to the 1850s. This is collodion wet plate, creating a large-format negative image on glass, not film. Sally says it was a a loving process of taking these photos. Her husband was very willing to help her complete this collection of him. Sally tended to take photos in which left the people in these photos looking vulnerable.

Sally said in an interview about these collections that it wasn’t so much abound his illness and his body slowing degenerating, but about a love story. When you look at the pictures you can’t help but notice his arm and leg, Larry was completely comfortable taking these pictures and showing these defects of himself off.

One picture specifically that Sally Mann says really spoke to her is called Tender Mercies. She says it actually brought tears to her eyes and she didn’t know if she ever wanted to publish it. It showed her husband as someone who was bigger then he actually was, bloated, sick, and weak. Someone he was not. However, he encouraged her to publish it because these were strong picture’s that really spoke about what he has to go through.

Portrait of Julie

Sep 13th, 2024 by Ray Sparks

One of the several portraits Élisabeth Vigée LeBrun painted of her daughter, Self Portrait with Her Daughter, Julie is one of various meanings. Painted in 1789, it is a symbol of love for her daughter as well as a defense of herself. As someone who was close with the aristocracy, Vigée LeBrun was scrutinized during the early days of the French Revolution, before her flight from France.

This portrait is one that practically radiates maternal love and a deep tenderness between Vigée LeBrun and her daughter. It’s humanizing to see a mother and daughter like this, and it’s separating Vigée LeBrun from the harsh ideas about the bourgeoisie. Vigée LeBrun gives the viewer an insight into her close relationship with her daughter, as well. From what I’ve read in her memoirs, Vigée LeBrun and Julie were incredibly close. Given the strained relationship between Vigée LeBrun and her husband, Jean-Baptiste-Pierre LeBrun, Madam LeBrun ended up spending the most time out of the two of them with their daughter. In fact, after Vigée LeBrun and her husband separated, Julie stayed with her mother.

It’s practically impossible not to feel the affection Julie and Vigée LeBrun share for each other in this painting. Julie’s small arms tossed around her mother’s shoulders, and her little face nestled into Vigée LeBrun’s neck. Vigée LeBrun herself is holding her daughter close, smiling at the viewer. You can sense the love radiating from the two figures on the canvas,

As for its relevance to my own story, Vigée LeBrun and her daughter’s relationship was something that deeply intrigued me. The two were so close, especially in Julie’s younger years, and I wanted to capture some of that.

Flying Home: Harlem Heroes & Heroines (downtown)

Sep 13th, 2024 by llhannah

Name of Piece: Flying Home: Harlem Heroes & Heroines (downtown)

When Created: 1996

Where Created: 125th street station Harlem

Meaning Behind Painting: The painting was a mural to pay respect and acknowledge the great performers, painter, and sports figures from Harlem.

Medium: Mosaic tiles

Subject: Black inspirational figures in Harlem history who deserved recognition

Reaction to work: Work received incredibly well because of people’s love and appreciation for these important figures.

This work relates to the story I’m creating as it is apart of the protaginist story line in any relation to flying. More specifically the dream scene the flying was meant to portray the protagonist flying with those other inspirational figures. It’s an important feature as Faith had a speciality for drawing people flying.

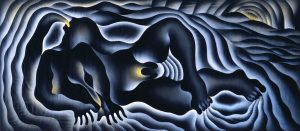

The Birth Project

Sep 12th, 2024 by qkgorman

- The Birth Project:

- This is one of many pieces that Judy Chicago made while collaborating with over 150 needleworkers.

- The work was a combination of paint and needlework.

- Chicago and the needleworkers created dozens of images surrounding motherhood and birth. They covered the painful aspects of it, the mythical feelings, and the beauty of motherhood. The project is meant to celebrate women’s ability to give birth and their knack for creativity in one project.

- Judy Chicago also created prints of some of the Birth Projects collection and her other works.

- This work is significant to the story as in my story Judy Chicago is already beginning to construct a rough idea of one of her famous pieces in the Birth Project.

- I used this artwork in my story because it symbolizes Judy Chic

ago’s realization that she misses working with paints and her interest in what women can do. In a way, it is meant to spur Judy Chicago’s realization that she as a woman can ask for more from men and her male partner.

ago’s realization that she misses working with paints and her interest in what women can do. In a way, it is meant to spur Judy Chicago’s realization that she as a woman can ask for more from men and her male partner. - I also used the painting to showcase Judy Chicago’s artistic side by implementing different colors and her creative mind into the story. I hoped to use this budding ‘idea’ to incorporate rich language in describing the artwork to give Judy Chicago more authority.

Bigmay Hood

Sep 11th, 2024 by qkgorman

This is the Bigamy Hood by Judy Chicago. It was made in 1965, two years after her husband’s shocking and abrupt death. Bigamy Hood is an abstract artwork created using Acrylic lacquer and then sprayed with acrylic support, following that, a fusion of color and surface occurs. The artwork symbolizes the severed connection between Chicago, her father, and her husband. The work came from the death of both her father and her husband. The work includes a broken heart and two crosses. This work was done during the time that Judy Chicago was dealing with her trauma and an identity crisis due to her husband’s loss and her past trauma with her father’s death. After releasing the work to the public Chicago faced criticism for the use of genitalia and called the work crass and oversexed.

This is the Bigamy Hood by Judy Chicago. It was made in 1965, two years after her husband’s shocking and abrupt death. Bigamy Hood is an abstract artwork created using Acrylic lacquer and then sprayed with acrylic support, following that, a fusion of color and surface occurs. The artwork symbolizes the severed connection between Chicago, her father, and her husband. The work came from the death of both her father and her husband. The work includes a broken heart and two crosses. This work was done during the time that Judy Chicago was dealing with her trauma and an identity crisis due to her husband’s loss and her past trauma with her father’s death. After releasing the work to the public Chicago faced criticism for the use of genitalia and called the work crass and oversexed.

The work is significant to my story due to the connection and crisis that Chicago had after her husband’s death. Following their impromptu 1959 road trip from L.A. to New York, Judy Chicago and Jerry separated again and it was their longest break. However, Jerry Gerowtiz and Judy Chicago got back together again and still had many issues in their relationship. Right before his death Chicago and Gerowitz had a huge argument and did not makeup. Chicago developed many issues due to that fact.

Marie Antoinette in a Chemise Dress

Sep 11th, 2024 by Ray Sparks

The painting Marie Antoinette in a Chemise Dress by Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, painted 1783, is a graceful and delicate portrayal of the famous queen of France. Vigée Le Brun’s skill in portrait painting was unmistakable to anyone who saw her works. At fifteen, according to her memoirs, she was already painting portraits and mingling with great artists. Her talent was so remarkable that she became the most well-known portraitist for Marie Antoinette, painting over thirty portraits of the Queen.

The painting Marie Antoinette in a Chemise Dress by Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, painted 1783, is a graceful and delicate portrayal of the famous queen of France. Vigée Le Brun’s skill in portrait painting was unmistakable to anyone who saw her works. At fifteen, according to her memoirs, she was already painting portraits and mingling with great artists. Her talent was so remarkable that she became the most well-known portraitist for Marie Antoinette, painting over thirty portraits of the Queen.

Marie Antoinette in a Chemise Dress is a stunning portrait. However, the painting of the Queen innocently arranging flowers in a plain white dress caused a large stir in the high art societies of eighteenth-century France, and not in the way Her Majesty or Vigée Le Brun had hoped. In fact, there was such an uproar about the portrait that it had to be removed from the Salon. Additionally, Vigée Le Brun ended up making an updated version of the painting, but I will return to that in a moment.

The reason for the upset surrounding the painting had to do with the “chemise” style dress Marie Antoinette was wearing. There were two things wrong with it. First, was that the dress was made of imported cotton muslin as opposed to French Lyonnaise silk, making it an insult to the country. Second, was that French royalty’s fashion was meant to be exquisitely extravagant at that time. To portray the Queen in something that looked similar to undergarments was scandalous at best.

And so, Vigée Le Brun repainted it. She made a new version with Marie Antoinette standing in a garden holding flowers while wearing an intricate and lacy blue silk gown. This painting, entitled Marie Antoinette with a Rose, was far better received by the courts.

In my own story, the connection to the first portrait is rather simple. Vigée Le Brun is in the process of painting it as the story begins. In her memoirs, she states, “It may well be imagined that I preferred to paint [Marie Antoinette] in a plain gown and especially without a wide hoopskirt.” I reference this line in the first few paragraphs, as it stuck out to me while I was reading Vigée Le Brun’s memoir. It was a pattern with her, that she preferred to paint women in comfortable clothes with layers of shawls and scarves.

One small detail is that Marie Antoinette wears a bronze, sheer sash tied around her natural waistline in the portrait. In all of Vigée Le Brun’s paintings I could find, I saw that sash appear in one other painting: Vigée Le Brun’s Self-Portrait in a Straw Hat. If you look closely, it’s the exact same sash. At first, I thought Vigée Le Brun might use the sash in several works, like the yellow mantle in Vermeer’s paintings. However, as I said, the only two I could find were that self-portrait and Marie Antoinette in a Chemise Dress. A tiny detail, but one I wanted to utilize nonetheless.

Camille Claudel and The Age of Maturity

Sep 9th, 2024 by ssraney

Camille Claudel’s The Age of Maturity (L’Âge mûr) stands as one of her most significant sculptures, deeply intertwined with her personal life and artistic journey. Created between 1893 and 1900, this piece is often interpreted as an emotional response to her relationship with Auguste Rodin, the renowned sculptor who played a pivotal role in her life. During the years Claudel worked on The Age of Maturity, her relationship with Rodin was deteriorating, particularly because he refused to leave his long-term partner, Rose Beuret. This rejection weighed heavily on Claudel, and her anguish is palpable in the symbolism of this work.

The sculpture itself features three figures: an older man being pulled away by an older woman, while a younger woman kneels in despair, reaching out toward him. The older woman, often seen as a representation of Rose Beuret, pulls the man toward her, while the younger woman—believed to symbolize Claudel herself—desperately tries to hold on to him. The man, who many assume to be a representation of Rodin, seems torn but is ultimately drawn away, leaving the younger figure behind. This sculpture is widely viewed as a reflection of Claudel’s personal experience of being abandoned by Rodin, and its emotional intensity captures the essence of loss, betrayal, and the passage of time.

The creation of The Age of Maturity was not without controversy. While some acknowledged the brilliance of Claudel’s work, others saw it as a direct criticism of Rodin. There are even suggestions that Rodin intervened to prevent the French state from acquiring the sculpture, an act that only deepened Claudel’s feelings of abandonment and professional isolation. This isolation, combined with her growing emotional instability, eventually led to her withdrawal from the art world and her tragic confinement in an asylum later in life.

In my story, The Age of Maturity plays a crucial role in reflecting Camille Claudel’s inner turmoil. Just as the sculpture depicts a woman left behind, desperately reaching for someone who has already turned away, Camille’s experience with Rodin in the narrative mirrors this painful separation. The emotions encapsulated in the sculpture—desperation, longing, and the inevitable loss—echo the themes I’m exploring in my portrayal of her life and work.

The sculpture serves as a metaphor for the emotional and creative struggle that defines Camille’s existence in the story. Her art, like The Age of Maturity, becomes an expression of the tension between love and abandonment, creation and destruction. By incorporating the emotional resonance of this sculpture, I aim to deepen the reader’s understanding of Camille’s fragmented mental state and the immense toll her relationship with Rodin took on her psyche. In a sense, The Age of Maturity represents not just a pivotal moment in her artistic career, but also the breaking point in her personal life—a poignant reminder of what she lost, both in love and in art.

Comte Charles Alexandre de Calonne by Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, 1784

Sep 9th, 2024 by Rhiannon

This particular portrait is of Calonne, the minister of general finances for the French King, which is what the letter in his hand portrays. It states the words Au Roi (To the King), symbolizing the royal confidence with which he was given and emphasized his importance within the royal court. The painter is also described to have captured the mans likeability. It is, once again, a neoclassical portrait done in oil paints on canvas, as this was Le Brun’s preferred medium.

This particular portrait is of Calonne, the minister of general finances for the French King, which is what the letter in his hand portrays. It states the words Au Roi (To the King), symbolizing the royal confidence with which he was given and emphasized his importance within the royal court. The painter is also described to have captured the mans likeability. It is, once again, a neoclassical portrait done in oil paints on canvas, as this was Le Brun’s preferred medium.

This painting was selected for the year it was painted, 1784, as a tension point that references Le Brun’s negligence during her first pregnancy with her daughter, Julia. She is noted, in one of her memoirs, that she had continued to paint well into her pregnancy and had not put much thought into when she was to conceive. She didn’t even have a doctor on hand until a family friend introduced one into the household.

I also wanted to use this piece as a choice of trying to convey certain details, like the usage of Saint Pantaleon, who was the patron saint of physicians and midwives. I thought it a cheeky wink and a nod, considering the topics I’m trying to convey and explore through this piece. I also used the powder wig of Calonne’s to reference Le Brun’s rather strong dislike of powders being worn by her models. This piece in general was used as a means of trying to introduce little details that make a person; her intense focus on her paintings to the point of neglecting her health, her strong preferences when it came to painting her models, the sheer exposure her role as a portraitist gave her in the way of connection, etc.

Portrait of Marie-Gabrielle de Gramont, Comtesse de Caderousse by Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, 1784

Sep 9th, 2024 by Rhiannon

The painting is about Marie-Gabrielle de Gramont, Comtesse de Caderousse. It is painted on an oak panel, using oil paints as the medium, in the Neoclassic style which Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun was noted to have contributed heavily to.

The painting is about Marie-Gabrielle de Gramont, Comtesse de Caderousse. It is painted on an oak panel, using oil paints as the medium, in the Neoclassic style which Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun was noted to have contributed heavily to.

In Le Brun’s memoirs, she notes that she persuaded the Duchess to not wear powder, which was a popular beauty standard of the time, so that Le Brun could showcase the beauty of her black hair. The painting, which showcases the Duchess as a peasant girl carrying a basket of fruit, was inspired by a fashion of rustic simplicity which was introduced by Marie Antionette herself.

The painting was done in 1784, the same year that Elisabeth lost her second child, which is mostly the reasoning as to which I chose this particular painting to involve in my story. It also linked well, purely on accident, because this painting also evoke fertility, the spring, and the renewal of things. The red flowers on the Duchess’ shoulder reflect a various set of meanings, but typically red flowers are used to symbolize love and romance, which is the source of all grief in many ways. The veil which extends from her hat also is capturing a tone which I set my first sentence of my story too.

Marie-Denise Villers’ Self Portrait

Sep 9th, 2024 by Phoenix

Self Portrait was first introduced to the world in 1802 at the Paris Salon. Marie-Denise Villers, being one of the only thirty women to present artwork at the Paris Salon, displayed various artworks she had produced within the past few years. The Self Portrait is a depiction of Marie, who is seemingly tying her shoes. While this painting is to depict herself, she used a model for the hands and different aspects of the body. When she accredited the model, Marie-Louise Soustras, for the use of her figure, this led people to mistake the model as being the entire subject in the painting for many years. For nearly a whole century, this painting was known as the Portrait of Madame Soustras.

Being known for portraits, this painting depicts many of the same themes she had explored with her other portraits. She creates detailed images of women during the neoclassical period. Her art is most praised for the amount of detail within face and clothing. With this piece in particular, we can observe the details within the dark lace of her attire. This was much more detailed and realistic compared to other words in her time. This fashion, also is a huge tell of the fashion in post revolution times. We can observe common use of lace and darker colors.

Being known for portraits, this painting depicts many of the same themes she had explored with her other portraits. She creates detailed images of women during the neoclassical period. Her art is most praised for the amount of detail within face and clothing. With this piece in particular, we can observe the details within the dark lace of her attire. This was much more detailed and realistic compared to other words in her time. This fashion, also is a huge tell of the fashion in post revolution times. We can observe common use of lace and darker colors.

There is a lot of detail in this piece. These details speculate just exactly what Marie-Denise Villers wanted to convey. To the left, we can see a freshly plucked flower in the hand of an empty glove. This could be dismissed as the addition of a garden lover, or this flower could symbolize something more important, such as the aspect of romance and flourishment.

While my story isn’t centered around this particular piece, this portrait creates a vivid image of Marie-Denise Villers. I believe this piece not only depicts Villers’ beauties, but also her character and themes as an artist. This helps me develop her as a character and bring her to life.

Marie-Denise Villers’ Portrait of Charlotte du Val d’Ognes

Sep 9th, 2024 by Phoenix

Marie-Denise Villers’ Portrait of Charlotte du Val d’Ognes is credited to be her most famous work to date. This portrait depicts a young woman, Charlotte, sitting in front of a broken window with a canvas in hand. Similarly to other works of Villers, this piece had been mistaken as a work by one of her mentors, Jacques-Louis David, for many years following its release to the public. This mistake overshines many of Villers work as they are credited to David. There is much speculation that there still remains works of Villers that are credited to David, or various other artists.

While Marie has created multiple portraits of Charlotte, there is not much known about the young woman. While her age is presumably a late teenager, 17-18, there is not much known about her as an individual. Marie Villers was said to be a close friend of the Val d’Ognes family, however her relationship with this family remains to be unknown. Since such little is known about the life of Charlotte du Val d’Ognes, Charlotte is only known for her presence in these paintings.

While Marie has created multiple portraits of Charlotte, there is not much known about the young woman. While her age is presumably a late teenager, 17-18, there is not much known about her as an individual. Marie Villers was said to be a close friend of the Val d’Ognes family, however her relationship with this family remains to be unknown. Since such little is known about the life of Charlotte du Val d’Ognes, Charlotte is only known for her presence in these paintings.

Marie remained in Paris for most of her years, and this is where it is presumed her work was completed, including the Portrait of Charlotte du Val d’Ognes. Her work was done predominantly in the early 1800’s, right after the french revolution. While she lived as a french artist, this portrait now resides at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, after the museum bought it in 1917. When this painting was purchased, it was known as the “the New York David”, since it was still believed at this time that David was the artist to give praise too. It wasn’t proclaimed until 1995, when a historian was able to tie this portrait back to Marie-Denise Villers’, as a piece of Villers.

This portrait is the basis for my story this week, as I try to capture the mystery behind Charlotte du Val d’Ognes and her relationship with the artist. I find her mystery compelling and believe that the answers to Charlotte lie within the Portrait itself, if just looked at hard enough.

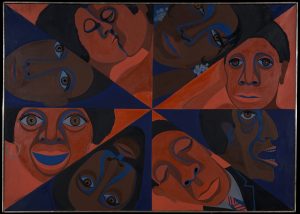

Faith Ringgold’s Black Light Series #11 US America Black

Sep 9th, 2024 by llhannah

Name of Piece: Black Light Series #11 US America Black

When Created: 1969

Where Created: Europe

Meaning Behind Painting:

Medium: Oil paints

Subject: Black facial features and the tones, the colors of melanated skin, and the experience of being a black woman in America

Reaction to work: Many received her work well especially though it was presented in the Spectrum Gallery in New York in the

This work relates to the story I’m creating as it is the catalyst that allows her to view her life differently. The art piece is meant to be a start for the character as she watches her own development into a black woman and an artist and with this journey, we’re seeing the progression of Faith’s work and how it molds the character’s vision of the world. This piece not only serves as Faith’s jump into art activism but also puts the main character’s way of life under a new lens and starts experimenting with ways of activism with her art.

Camille Claudel’s The Waltz and the Art of Inner Turmoil

Sep 8th, 2024 by ssraney

The Waltz (La Valse) by Camille Claudel is a crucial work in her career, created between 1889 and 1905. This bronze sculpture beautifully captures human emotions and movement with remarkable detail. It portrays a couple engaged in a close, swirling dance, their bodies intertwined in a way that suggests intimacy and tension. The fluidity of their forms emphasizes their connection, while the subtle positioning of their bodies and closeness conveys a powerful sense of love and longing.

At the time of its creation, The Waltz stirred controversy. When Claudel first submitted the work for purchase by the French government, it was rejected for being “too sensual.” The closeness of the figures, especially the woman’s flowing gown, which appeared to reveal too much, was deemed inappropriate. Claudel was forced to modify the sculpture, making the woman’s dress more modest before it could be exhibited. This incident highlights the difficulties she faced as a female artist, where her work was often scrutinized and overshadowed by the male-dominated art world and her relationship with Auguste Rodin.

The inspiration behind The Waltz is closely tied to Claudel’s complex relationship with Rodin, who was both her mentor and lover. Many see the sculpture as a reflection of their relationship’s ups and downs the passionate connection between the dancers mirrors the passion she shared with Rodin, while the tension in their embrace hints at the conflicts and difficulties within their love. The swirling movement of the figures conveys a sense of dizziness or instability, reflecting Claudel’s struggles with her mental health and her eventual separation from Rodin.

In my story, The Waltz serves as a symbol of Camille’s inner world—her passionate yet troubled relationship with Rodin. The sculpture reflects her desire for emotional closeness but also highlights the instability that defines their love. By focusing on the creation of The Waltz in my narrative, I can explore the emotional and mental toll this relationship took on Camille, using the sculpture as a metaphor for her unraveling.

The tension and discomfort I want to evoke in my story align perfectly with the themes of The Waltz. Its reception—celebrated for its beauty but criticized for its sensuality—mirrors Camille’s experience as an artist fighting for recognition. The sculpture represents more than just art; it’s an extension of Camille’s emotional world, her artistic voice, and the turmoil she faced in her relationship with Rodin. Including this historical context will add layers to my story, allowing the reader to better understand Camille’s inner conflict.

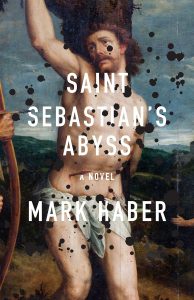

Friend or foe?

Sep 6th, 2024 by qkgorman

Upon first reading this book it was almost unbearable to finish. The level of condescending and droning made it hard for me to finish the book. One of the hardest parts of the book was reading about Schmidt’s many attempts to sabotage and trash-talk the main characters’ work. In a way, each time that Schmidt tried to discourage the main character from achieving more, I as a reader got more hooked on the story. I believe that is because of the impending tension of the main character finding out that Schmidt was never his friend.

Upon first reading this book it was almost unbearable to finish. The level of condescending and droning made it hard for me to finish the book. One of the hardest parts of the book was reading about Schmidt’s many attempts to sabotage and trash-talk the main characters’ work. In a way, each time that Schmidt tried to discourage the main character from achieving more, I as a reader got more hooked on the story. I believe that is because of the impending tension of the main character finding out that Schmidt was never his friend.

Within the first opening chapters, the main character mentions that he believes that Schmidt had a hand in both of his divorces. This is further solidified when we learn how he treated both wives. With the main character’s first wife, after learning about her disinterest in paintings, Schmidt turned his nose up at her. Schmidt then stood up and excused himself, citing a forgotten appointment, making it very clear that there was no appointment. With the main character’s second wife, Schmidt claimed that she had dedicated her life to trash because she was a professor and critic of modern art. Schmidt believed that all “good art” died in 1906 when the famous painter Cezanne died. Schmidt went so far as to ask the wife: “How does it feel to know you dedicated your life to trash?”. To me, it seemed like Schmidt was trying to say the most hurtful things to disrupt the main character’s marriage.

In addition to that Schmidt took his time to brag about how his second choice in painting is better than the main character’s and the main character lets Schmidt believe that. Schmidt accredited his superior judgment of paintings to being from Austria and taking the time to call the main character uncultured because he is from America. On top of insulting the main character, he explained that America raises only imbeciles because it is devoid of rich historical nutrients. Schmidt believed that all American art critics are nutrient-starved and dense.

All of this was confirmed to me by the final chapters of the novel. Schmidt took the time to continue insulting the main character and holding the fact that he knew the ‘final meaning’ of Saint Sebastian’s Abyss over the main character’s head. He also took the time to put down both of their writing, but he put the main characters’ writing lower than his again. The entire final chapter gives off the impression of a bitter dying man who continues to lash out at the one man who stuck with him through all of his rambling and condescending comments. Schmidt’s character, although incredibly important to the story, made the entire story very hard to continue reading.

Friends to Enemies

Sep 6th, 2024 by amsmith

From the very beginning of Saint Sebastian’s Abyss, we see how close Schmitt and the narrator are, whose name we never know. We see their relationship unfold into a clump of hatred they both have towards each other. Both very intelligent men, who have such a passion for art, yet such difference of opinions on different painting’s. How could this be if they were always the best of friends?

The narrator held on to false hope of Schmitt finding out what the letters meant though all these years, maybe so they could catch back up and rekindle their relationship. Once Schmitt dies and he finds out how close he was to finding these unforgotten letters at the bottom of the painting of Saint Sebastian’s Abyss, part of him dies too. All these years of hatred and friendship for nothing. To realize the one thing they were most passionate about just died with Schmitt.

Once the death of Schmitt, he seeks and hunts to find out what the clues Schmitt left mean, which lead to nothing. An emptiness he feels as he cannot find the most important thing he longs for. After years of obsessing over this painting he eventually feels nothing. He is gutted. I think he realizes he lost one of the most important people in his life a long time ago, but realized it when it was to late. Therefore that’s why he feels empty and the last time he looks at the painting, its as if he is looking at a blank canvas. The person he enjoyed the most was not there to give him a hard time, or even bond over their love for this painting. Instead he is left with many questions that will never be answered or thought of again.

Bromance and Codependency as Seen In Saint Sebastian’s Abyss

Sep 6th, 2024 by Phoenix

Saint Sebastian’s Abyss is a true testament to just how far a bromance can go. Bromance, as defined by the Merriam Webster dictionary as “a close nonsexual friendship between two men”, is a term that can be used to describe the complex relationship between two men presented in the story. Haber’s narrator who navigates the history of his intense bromance with his scholarly companion, Schmidt, is faced with the mortality of his long term friend. While deeply reflecting his past, our narrator remains unnamed and seemingly ties all of his life to Schmidt in one way or another. It seems that his identity is so deeply intertwined with his decades long relationship with Schmidt, that he cannot identify himself as an individual. While as readers we do not learn our narrator’s true name or his true nature beyond Schmidt, we can observe his codependent nature closely.

A “Bromance conundrum” is “when your heart is torn between two loves: your spouse and your best bro”, as defined by Remy Bluemfeld in The Hollywood Reporter. Our narrator navigates this conflict with both of his ex wives and Schmidt in a cowardly nature, in which he refuses to dispute Schmidt’s arrogant and discourteous acts towards his wives. This is a clear characterization of not only Schmidt, but our narrator. Our narrator becomes known through these actions as conflict avoidant, in which he seems to be unable to simply tell Schmidt that he is a pretentious asshole. It is this conflict avoidance that leads Schmidt and our narrator to their inevitable downfall when after decades, our narrator says the “terrible, no good, very bad thing”.

A “Bromance conundrum” is “when your heart is torn between two loves: your spouse and your best bro”, as defined by Remy Bluemfeld in The Hollywood Reporter. Our narrator navigates this conflict with both of his ex wives and Schmidt in a cowardly nature, in which he refuses to dispute Schmidt’s arrogant and discourteous acts towards his wives. This is a clear characterization of not only Schmidt, but our narrator. Our narrator becomes known through these actions as conflict avoidant, in which he seems to be unable to simply tell Schmidt that he is a pretentious asshole. It is this conflict avoidance that leads Schmidt and our narrator to their inevitable downfall when after decades, our narrator says the “terrible, no good, very bad thing”.

Even after their fallout, our narrator and Schmidt seem to still obsess over each other, by closely studying their writings and speeches and dissecting them to the point where it seems as if their worlds are no longer about the painting of Saint Sebastian’s Abyss, but rather about their complex feelings towards each other. This complexity follows both characters throughout their lives so closely, that it consumes their livelihood. It seems to lead our narrator to the ending of his two marriages, and Schmidt to no livelihood at all. This bromance, and obsession, seems to destroy their lives and any true chance at happiness.

Thoughts on Saint Sebastian’s Abyss

Sep 6th, 2024 by llhannah

The Characters and their Journey

The characters in Saint Sebastian’s Abyss are deeply connected to the story’s themes of redemption and self-discovery. The main character struggling with inner conflict and seeks meaning in his life, which drives the plot and reflects his quest to reconcile his past with his present. Other characters in the novel help to highlight different aspects of the protagonist’s journey. Their interactions reveal various challenges, like the need for forgiveness and dealing with unfulfilled dreams. These relationships were key to me understanding the protagonist’s growth and how he sees himself and his place in the world. Overall, the characters in Saint Sebastian’s Abyss add depth to the story. Their personal struggles and growth make the novel’s themes more powerful and ponient, making the reading experience thought-provoking.

The Writer’s Craft

The author created a great narrative that delves deeply into the protagonist’s psyche, from introspective prose to exploring themes of redemption and existential struggle. The novel’s use of symbolism, particularly the recurring motif of the abyss, serves as a powerful metaphor for the protagonist’s inner journey and the deep emotional and psychological depths he must confront. Through carefully crafted dialogue and vivid imagery, the author not only brings the characters to life but also immerses readers in their struggles, creating a compelling and reflective reading experience. However overshadowing the characters’ personal stories with its grand metaphors. There is an overemphasis on symbolic imagery that detractcted me from the narrative’s emotional impact, making certain passages feel more like abstract ramblings rather than compelling storytelling.

You Must Be Fun at Parties

Sep 6th, 2024 by Ray Sparks

As I read Mark Haber’s Saint Sebastian’s Abyss I kept finding myself chuckling under my breath at the narration. I’d stop and read amusing passages to my friends around me aloud, sharing in the satirical nature of it all. Haber has managed something here that I wonder if was intentional. The voice our narrator uses is a drummed-up version of the stuck-up art snob. When I first began reading this book, I wondered how on earth over ten separate books could be written by two people, not repeating themselves, or each other, over one small painting. The narrator and Schmidt would probably tell me that I was being primitive and not thinking enough about the true beauty of the painting Saint Sebastian’s Abyss.

However, as I read, I realized I wasn’t so far off base. There’s no possible way those books lacked repetition because the narration is filled with repetition. When I write, I try rather hard to avoid repeating myself too much, as it can come across as dull or just trying to blurt out a word count. Yet, the repetition in Saint Sebastian’s Abyss doesn’t feel dull to me. If anything, it adds extra flavor to the book. We see our narrator’s style of speaking or writing throughout the pages, and we begin to understand just how he rambled on for over five books worth of material about one small painting. I was thoroughly impressed by Haber’s ability to use this repetitive speaking to his advantage without boring me to death.

Another element of this book I truly enjoyed was the narrative style. I’m reminded of my argument against my classmates in my high school freshman-year English class in defense of J.D. Salinger’s Catcher In the Rye. I don’t mean to preach some greater understanding of literature, but I found it frustrating when others didn’t understand Holden’s character wasn’t meant to be liked. I understand the urge for a likable and good protagonist, but I’ve always loved the picture-perfect example of the unreliable narrator Catcher In the Rye portrays. Shooting off of that, the narrator in Saint Sebastian’s Abyss is someone I’m not sure I’d get along with in real life. I know for certain I wouldn’t get along with Schmidt. Still, I enjoyed reading about them.

There’s a certain air of satire to the narrator and Schmidt. They almost feel like caricatures of art fanatics. Yet, I couldn’t help but find their strange mannerisms entertaining. Perhaps that says something about me and how I view the world. Or, perhaps, it says more about Haber.

Percieved Difference

Sep 5th, 2024 by Amara Clancey

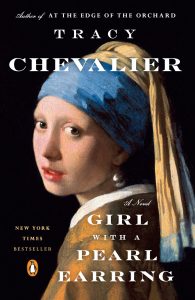

The Girl with the Pearl Earring.

The very first scene is important when considering how the characters will interact with each other for the rest of the novel. The author does a remarkably ood job of making it clear the basic characteristics of each person. Greet is a perfectionist, Caterina is clumsy and foolish, Vermeer is blunt and inquiring. Religious differences are extremely important to the plot of this story. The initial perceived strangeness of Vermeer and his family as Catholics compared to Greet as a Protestant, as well as the shift to familiarity with Vermeer when she discovers that he is secretly Protestant as well, creates a level of relation that their joint appreciation of art did not quite accomplish.

While they both love art, they sThee it in very different ways (note her confusion regarding the camera obscura), her perception of it is that of a tile maker’s daughter- desiring both great beauty and practicality, as well as a certain level of sadness in its relation to her father and his ability (and now, lack thereof). In contrast, his is that of a painter- beauty with a lack of practicality, as well as the beauty being tainted by a level of responsibility or requirement- he needs to produce art, he can’t choose not to, or even sometimes, what to produce.

Greet’s discomfort with many of the paintings displayed in the house (The Crucifixion, the painting in her cellar room) contrasted to Vermeer’s creations, to me, represents a certain discomfort with the way he presents himself and his family versus how she believes he truly is. This of course returns to the contrast of comfort and discomfort with Protestantism and Catholicism.

Are We Still Friends?; Performative Friendships, Toxic Masculinity, and Taking Yourself Too Seriously

Sep 4th, 2024 by Rhiannon

Saint Sebastian’s Abyss by Mark Haber is an interesting read that reflects the mind of a rather peculiar man, one whose visually succinct thoughts seem to take up pages more by sheer density of word and meaning alone. One can almost see how this man, our protagonist, managed to milk almost a dozen books, book length essays, and multiple lectures and public topics out of a single painting.

There are several topics I could speak about, perhaps at length, on the ideas that were explored within this book – but I’ll focus on the perspective of performative friendship, toxic masculinity, and what self-importance can do.

The first thing I want to take into account is Schmidt, because I feel as though of these two characters, he is the driving force in which a majority of these issues take root. He is portrayed to us as a particularly sickly man, infirm and riddled with a great many maladies that almost read to me as the root of some of his behavior. There is a great deal of self-importance in Schmidt, his demands that it was him who saw the painting of Saint Sebastian’s Abyss, how he thinks of the two critics it is his opinions, his thoughts, that must be treated with greater weight. He comes from Austria, a place he deems greatly cultured and greater than most, and he is tolerant of the American protagonist and his opinions, for his opinions are weighed and directed only by how well they match with Schmidt’s opinions.

When the American narrator expresses a single opinion outside of Schmidt, how art is interpretative, Schmidt destroys their bridges and begins a rather tyrannical reign of attempting to tear apart the narrators work, opposing him and isolating him like he’s done the narrators whole life – especially with his marriages.

Schmidt, rather actively and passively, ruins the narrators relationships with his opinions and dislike for anything outside of a shared passion. Both wives expressed a dislike for Schmidt simply because of his character, the first wife noting that Schmidts flood of emotions was liable to be a performance simply so he could outperform the narrators supposed closeness to this particular painting. The second wife expressed differing art opinions, a lover of that which was modern, while Schmidt took an interesting stance that ‘true’ art died in 1906.

To me this read as both a jealousy of what the narrator had, an emotional love for this painting and the capacity to exist outside of it, to live happily without Schmidt, that Schmidt refused to accept. Schmidt thinks that his opinion is of the only worth, and it is here where I think that the performative friendship and toxic masculinity expresses itself.

In the narrator, Schmidt likely see’s him like he see’s America itself, young and uncultured. He likely also see’s, from his seat of self importance, a sycophant of some interpretation. Schmidt’s identity and whole life is wrapped up in this single painting, and he wants the narrator there with him, to sit fully as enraptured as Schmidt perceives himself to be because to be a art critic is to make a stance and opinion at the cost of ostracizing everyone else. He refuses to accept a world outside of his own view, which I think is a rather common masculine trait in those who feel the need to project power when they themselves lack it.

Schmidt’s ‘friendship’ with the narrator, through this lens of self importance and flattering the ego, then takes a different turn. It is less about friendship, and more about enabling, of flattering Schmidt’s ego. An ego that is rather fragile, for he must condemn and rant and rave that no other art truly exists compared to Saint Sebastian’s Abyss, as we see with how he treats other artists or other appreciators of art like the narrators two ex-wives. Their opinions jeopardized Schmidt’s place and value of opinion in the narrators life.

It’s a very interesting dynamic because it feels like Schmidt has introduced the narrator to the concept of a contemporary at it’s most extreme, and without Schmidt, he doesn’t quite have the same passion — having a man you were once deep ‘friends’ with and sharing obsessions with tearing your work apart could also contribute — and does not wish to continue as he once did. This whole novel the narrator reminisces, and then ends with a abrupt cut thread, a blow to his passion again because Schmidt in his pursuit to be the greatest mind to interpret the beauty of Saint Sebastian’s Abyss could not leave their relationship well enough alone. He demanded to have the last word, to rehash an old hurt they had gone over again and again, and then died because his zealousness over learning the truth of the signature on the painting. Once again trying to prove his superiority, to reinforce that the narrator was nothing in comparison.

What Would You Do For Love?

Sep 4th, 2024 by amsmith

The story On Little Terry Road by Tom Franklin is nothing short of a love story. A cop falling for a troubled young girl and will stop at nothing to keep her safe. Ferriday, the daughter of his dead ex-girlfriend, always finds herself in a predicament. Dibbs, a drunk also a cop in this small town, knows everything about everyone and does his best to save who he wants.

Throughout the story you understand more of Ferriday’s and Dibbs’s relationship. You can see how much he cares for her, but is it out of love or is it our of pity? He knows how her homelife was with her father and being sexually abused by him. He also was there when her mother died after years of not even knowing her really. The burden Dibbs had to ensure nothing ever happen to Ferriday was something he would hold onto for the rest of his life.

We come to know that even after she plead for his help, knowing he would do so, she leaves. Was it out of fear of not knowing? Was it because she knew he would handle it and she can move onto something else? Or was it because she was just simply scared? Dibbs knew the risk of losing his job, having to start a new life, and yet still chose to help Ferriday. He would do anything for this girl regardless of the repercussions and still be let down. Even after he finds out she has left, he still decides to cover up that she was even there at the motel.

This story just shows that people will do anything for love or even the hope of love. Part of me believes that he looked at Ferriday as her mother since she has now past. He doesn’t want to let Barbra go, so he holds on to Ferriday. Out of protection maybe, not wanting to to let her down again by another person she cares about. But I don’t think Ferriday cared at all. She would do anything that is best for her, where as Dibbs would do anything that is best for her too, without thinking of how it could affect himself.

The Damsel in Distress

Sep 4th, 2024 by qkgorman

“On Little Terry Road” by Tom Franklin was an extraordinary read. The damsel in distress and its parallel of using Dibbs as a scapegoat was a cunning and vicious turn of events. It was a fun and abnormal technique wielded by the author to elicit a visceral response in the reader. I was struck by the relationship between Dibbs and Ferriday. The utter desperation that Dibbs feels towards Ferriday and the lengths to which he will go to help her are intriguing and beguiling. In a way, Dibbs is a dangerous and desperate man with a compulsive need to help his stepdaughter.

“On Little Terry Road” by Tom Franklin was an extraordinary read. The damsel in distress and its parallel of using Dibbs as a scapegoat was a cunning and vicious turn of events. It was a fun and abnormal technique wielded by the author to elicit a visceral response in the reader. I was struck by the relationship between Dibbs and Ferriday. The utter desperation that Dibbs feels towards Ferriday and the lengths to which he will go to help her are intriguing and beguiling. In a way, Dibbs is a dangerous and desperate man with a compulsive need to help his stepdaughter.

As the relationship between Dibbs and Ferriday unfolded, I was enraptured by the backstory that Franklin revealed. Learning that Dibbs was technically Ferriday’s stepfather through his marriage to Barbara, I became more apprehensive of their frankly inappropriate relationship. Ferriday and Dibbs exhibit signs of sexual tension between the two, particularly from Dibbs’ side. It was hard to determine if Ferriday was genuinely attracted to Dibbs or if she was manipulating his repressed feelings to her benefit – perhaps it was both.

While a common cliche, Dibbs’ torment was that of a law enforcement officer forced to choose between the law and his desperate loved ones. The reader is lured into Dibbs’ dilemma as he attempts to compartmentalize the situation and justify his actions. The whole story is magnified the moment that Dibbs goes from an enforcer of the law to a criminal. The second that he walks into the house without calling it in, he commits a crime; however, if he called it in, he’d either have to tell the supervisors the truth and expose his stepdaughter to the consequences of her actions, or continue to lie and hope he doesn’t get caught. Dibbs chooses to enter the house and in the eyes of the law, becomes a criminal.

The final page of the short story was mind-blowing to me. The pure brutal way in which Dibbs leaves Little Terry to die knowing it’s likely that Ferriday used him to get away with her crime. The idea that Dibbs was okay with Ferriday using him as long as he felt that he could help or maybe he was enjoying the fact that she was asking for his help highlighted the lengths at which Dibbs was willing to go for Ferriday. Nonetheless, the fact that Dibbs sat there smoking a cigarette and waiting until he was sure that Terry was dead shows that he feels that he must save Ferriday from her actions.