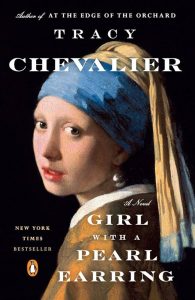

When I look at the first third of Tracy Chevalier’s The Girl with a Pearl Earring, I see a masterclass in carefully crafting historical fiction. As a writer, it’s impossible not to appreciate Chevalier’s deliberate choices in setting, characterization, and narrative voice, all of which contribute to the novel’s immersive quality and ability to transport readers to 17th-century Delft.

When I look at the first third of Tracy Chevalier’s The Girl with a Pearl Earring, I see a masterclass in carefully crafting historical fiction. As a writer, it’s impossible not to appreciate Chevalier’s deliberate choices in setting, characterization, and narrative voice, all of which contribute to the novel’s immersive quality and ability to transport readers to 17th-century Delft.

Setting as a Living Character

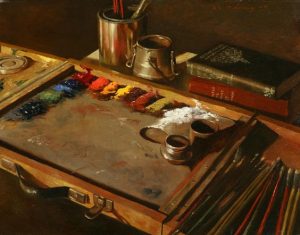

From the first pages, Chevalier’s attention to the setting is striking. Delft isn’t just a backdrop; it’s a character in its own right. The cobblestone streets, the markets, and the somber interiors of the Vermeer household are described with such detail that they feel alive. The artist’s studio, particularly, stands out to me as a writer. The way Chevalier uses the dim lighting, the arrangement of objects, and the quiet, almost sacred atmosphere creates a setting that mirrors Griet’s internal world—full of secrets, tension, and a sense of being trapped.

This focus on the setting early in the novel is a deliberate choice. By immersing readers in this world, Chevalier lays the groundwork for the characters’ struggles and desires to feel real and immediate. It’s a reminder that in historical fiction, the world-building must be so vivid and tangible that it not only grounds the story but also shapes it.

Characterization Through Subtlety and Restraint

Chevalier’s approach to characterization in the first third of the novel is a lesson in subtlety. Griet, the protagonist, is a young woman of few words but rich inner thoughts. Chevalier allows us into Griet’s mind, revealing her intelligence and sensitivity through her observations and inner monologue. As a writer, I admire the restraint here—dialogue is sparse, and much is left unsaid, which only adds to the tension. Griet’s conflicts—between duty and desire, family and self—are powerful because they’re so quietly portrayed.

Then there’s Vermeer, who remains distant and enigmatic. His presence is felt more through his art and the reactions of those around him than through direct interactions with Griet. This distance is a conscious choice by Chevalier, creating an air of mystery that makes their eventual connection more complex and intriguing.

For a writer, this subtle characterization is a reminder of the power of restraint. By showing rather than telling, by leaving things unsaid, Chevalier creates characters that feel real and layered, inviting readers to fill in the gaps and engage more deeply with the story.

The Power of Perspective

The choice of a first-person narrative, closely aligned with Griet’s perspective, is another deliberate craft decision that I find particularly effective. This narrative voice pulls the reader directly into Griet’s world, making her experiences and emotions feel immediate and personal. Chevalier’s use of this perspective also reflects Griet’s limited understanding of the world around her—she’s a young, lower-class woman in a society where her knowledge and power are constrained.

As a writer, I see the brilliance in this choice. By aligning the narrative voice so closely with Griet’s perspective, Chevalier not only heightens the emotional impact of the story but also creates a sense of suspense. The reader, like Griet, must piece together the intentions and desires of the other characters, which adds layers of complexity to the narrative.

Why it Matters

In the first third of The Girl with a Pearl Earring, Chevalier’s craft choices—the attention to setting, the subtle characterization, and the use of a first-person narrative—are not just about creating a believable historical world. They’re about crafting a story that resonates on multiple levels. By immersing the reader in 17th-century Delft, the past feels alive and relevant. By developing her characters with such care, she explores timeless themes of power, control, and identity. By choosing to tell the story from Griet’s perspective, she invites readers to see the world through her eyes, making her struggles and desires feel personal and relatable.

For writers, The Girl with a Pearl Earring offers valuable lessons in the art of storytelling. It’s a reminder that every element of craft, every choice we make, contributes to the overall impact of the narrative. Chevalier’s novel shows us that when these elements are used thoughtfully and deliberately, they can create a story that not only transports readers to another time and place but also resonates with them on a deeply emotional level.

On Little Terry Road, Ferriday is driven by addiction. This addiction drives her to Little Terry Road, which is declared to be “where you went if you wanted trouble” (Franklin 10). Often in literature, addiction can symbolize isolation, deception and despair, which could easily be argued to be a fair representation of Ferriday’s current state. Ferriday is seemingly alone, unable to depend on anyone else other than the narrator. She even claims that she had been forcing herself into isolation, away from him, to get sober. Her despair is a driving factor of how she got herself into danger, in which it drives her to try to get more substance.

On Little Terry Road, Ferriday is driven by addiction. This addiction drives her to Little Terry Road, which is declared to be “where you went if you wanted trouble” (Franklin 10). Often in literature, addiction can symbolize isolation, deception and despair, which could easily be argued to be a fair representation of Ferriday’s current state. Ferriday is seemingly alone, unable to depend on anyone else other than the narrator. She even claims that she had been forcing herself into isolation, away from him, to get sober. Her despair is a driving factor of how she got herself into danger, in which it drives her to try to get more substance.

Audubon’s Watch

Audubon’s Watch As a character, Griet is so well written, the more I read it the more I learned just how clever she is. One of her most amazing abilities is her affinity for colors and her frankly unexplained ability to identify what a painting is missing. For example; in the opening scene, when questioned about her strange placement about the ingredients for a stew, Griet explained that the color’s clashed when placed together. In addition when she was being painted, she was able to identify what the painting was missing before Vermeer could.

As a character, Griet is so well written, the more I read it the more I learned just how clever she is. One of her most amazing abilities is her affinity for colors and her frankly unexplained ability to identify what a painting is missing. For example; in the opening scene, when questioned about her strange placement about the ingredients for a stew, Griet explained that the color’s clashed when placed together. In addition when she was being painted, she was able to identify what the painting was missing before Vermeer could.

The way the paintings are described is the most poetic to me. The language Chevalier uses conveys the sort of feeling a Vermeer evokes. To capture the style of a true master of a visual craft in words is incredibly skillful, to say the least. It was the assortment of colors, lights, and shadows that constructed the most magnificent parts of this book. The reader is brought with Griet to learn about all the colors her, and our, world have to offer us.

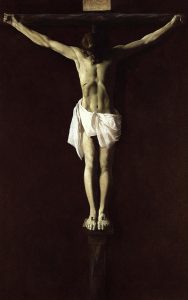

The way the paintings are described is the most poetic to me. The language Chevalier uses conveys the sort of feeling a Vermeer evokes. To capture the style of a true master of a visual craft in words is incredibly skillful, to say the least. It was the assortment of colors, lights, and shadows that constructed the most magnificent parts of this book. The reader is brought with Griet to learn about all the colors her, and our, world have to offer us. A significant conflict in this story for not only Griet, but much of 16th century Europe, is the division between religions. Griet, coming from a Protestant family, is unfamiliar with the Catholic religion and its followers, being only surrounded by a Protestant community throughout her young life. Much of her own troubles with the Catholic religion is manifested into fear. This fear becomes a deep issue for Greit as she is introduced into a family of Catholics as their maid. It is important to remember that much of the Protestants and Catholics at this time did not coincide with one another, and instead found their religion to be a piece of their identity and culture. This contributed greatly to the social division between the two communities in Europe. Griet finds this piece of identity to be one that forms them to be completely different then herself. As she is introduced into the house of Catholics, she thinks of herself as “outnumbered” (Chevalier 31). Greit seems to carry a strong form of ‘Me vs. Them’ mentality, weaponizing her own religion against the family she works for. This ideology represents much of the communities in Europe in this century, in which these two different groups of people use their faith against one another.

A significant conflict in this story for not only Griet, but much of 16th century Europe, is the division between religions. Griet, coming from a Protestant family, is unfamiliar with the Catholic religion and its followers, being only surrounded by a Protestant community throughout her young life. Much of her own troubles with the Catholic religion is manifested into fear. This fear becomes a deep issue for Greit as she is introduced into a family of Catholics as their maid. It is important to remember that much of the Protestants and Catholics at this time did not coincide with one another, and instead found their religion to be a piece of their identity and culture. This contributed greatly to the social division between the two communities in Europe. Griet finds this piece of identity to be one that forms them to be completely different then herself. As she is introduced into the house of Catholics, she thinks of herself as “outnumbered” (Chevalier 31). Greit seems to carry a strong form of ‘Me vs. Them’ mentality, weaponizing her own religion against the family she works for. This ideology represents much of the communities in Europe in this century, in which these two different groups of people use their faith against one another.

While the theme of obsession is prevalent throughout Butler’s story, where is it in the painting? Soir Bleu is often found to capture themes of isolation within the characters depicted. In the painting, we can see four uniquely dressed individuals, while all posed carefully together, are lonesome in their own aesthetics. We can see that the clown, dressed in a luminosity white attire and a painted face stands out the most. As the clown captures the eye for the aesthetic, there is also a look not familiar with the common stereotype of clowns. While clowns are typically depicted with a smile, the clown in Soir Bleu is nonchalant, boarding a look of sadness. As viewers, it is obvious that while the clown is surrounded by people, the clown is not particularly overjoyed by the company. The contrast of the clown’s apperence and those that sit with him at the table create a certain visual division between the four.

While the theme of obsession is prevalent throughout Butler’s story, where is it in the painting? Soir Bleu is often found to capture themes of isolation within the characters depicted. In the painting, we can see four uniquely dressed individuals, while all posed carefully together, are lonesome in their own aesthetics. We can see that the clown, dressed in a luminosity white attire and a painted face stands out the most. As the clown captures the eye for the aesthetic, there is also a look not familiar with the common stereotype of clowns. While clowns are typically depicted with a smile, the clown in Soir Bleu is nonchalant, boarding a look of sadness. As viewers, it is obvious that while the clown is surrounded by people, the clown is not particularly overjoyed by the company. The contrast of the clown’s apperence and those that sit with him at the table create a certain visual division between the four.